When it comes to sustainable fashion or how "green" a brand is, the conversation typically centers around whether a brand uses recycled fabrics, organic cotton, or something mushroom-related. If you look at the data and trends over the last thirty years and how we got here — these are all sustainable fashion myths.

Circularity initiatives like take-back programs and various certifications, like a B-Corp status or using Better Cotton Initiative certified cotton are also popular virtue signals. In reality, the narrative is full of sound and fury signifying nothing — it's not quite as transparent or sustainable as it appears. While the quality of a garment is exactly as it appears. Quality provides for a garment's durability, longevity, and extended reuse — which has the lowest global warming potential, not recycling.

During World War II when fabrics were rationed, the UK implemented something called the Utility Scheme to clearly communicate how well a garment was made by assigning a government issued grade to each item. The grade started with the cloth and extended to how well the final garment was constructed. Why? People needed to understand how well something was likely to last. Their ration coupons applied per garment so people wanted to understand what kind of value they were getting for each ration coupon as they needed clothing to last until the next ration cycle. Because the quality of the item translated directly to how long the garment would last.

Today, we rely on voluntary data, buzzwords, or third-party certifications gives an illusion of transparency and perpetuate various sustainable fashion myths. Countless studies have shown how ESG data is often cherry-picked or inaccurate, misleading, or simply meaningless. It's why investors are pushing financial regulators to create more stringent standards around ESG disclosures. Transparency should remove the need for trust. Companies make so many efforts to appear transparent, but the market isn't close to being transparent when it comes to ESG data, a problem I wrote about in this piece for The Fashion Law and when it comes fashion's sustainability certifications it's not different. Fashion's sustainability coverage largely ignores these well-documented data problems, ultimately enabling and rewarding greenwashing.

Fashion's current sustainability narrative and headlines rarely address the tangled roots of fashion's environmental offenses: the rise in volume, decline in quality, and broad underutilization of clothing. Quality is a fairly objective feature of a garment, one that helps maximize each garment's use. How a garment is constructed, what it's made is easily observable and doesn't require independent certification or trusting information from the brand. All you need is the garment itself. Transparency removes the need to trust.

Quality is the ultimate form of transparency. You can't greenwash quality — it simply is.

The False Comfort of Certifications

Sustainability is no longer a niche trend, but a necessary part of every mainstream corporate strategy. Consumers and brands want an easy or cheap solution to be more "sustainable" when in reality it's anything but. Certifications are a way to check that box often. In theory, certifications provide transparency and are a form of non-governmental self-regulation. In reality, certifications give the illusion of transparency — they create a sustainable fashion myth.

The Changing Markets Foundation found that certification schemes, "lower[s] the bar to certify higher product volumes and in many cases fails to enforce greater transparency, thereby providing cover for unsustainable companies and practices."

A recent investigative piece from the New York Times showed that fourth-fifths of Indian organic cotton isn't organic. Another study showed that garments made from recycled plastic didn't have any recycled content at all or significantly less than advertised. It wasn't until the wider Xinjiang scandal broke that the Better Cotton Initiative even addressed the issue of forced labor in the region.

The common element among certifications is that they rely on the consumer to trust the information from the company or the certifying body. Most consumers can't test whether their organic cotton tee shirt is, in fact, organic.

Third-party certifiers maintain varying degrees of opaqueness regarding their process, however. A study out of UC-Berkeley on the Higg Index noted that its lack of transparency hinders its potential effectiveness to promote better transparency in the apparel market. They also cite a previous and how "billions of dollars and many attempts at new environmental standards, codes, monitoring, and capacity building programs have failed to drive significant progress in the environmental performance of the apparel industry." Yet brands continue touting their certifications and the media keeps writing about them consistently overlooking that the data is voluntary and unaudited, thus largely meaningless.

Just because it can be measured doesn't mean it's meaningful.

One of the fastest-growing certifications is the B-Corp, which is marketed as a business classification but is a certification for a corporation's social and environmental aspirations. "B Corp standards are not legally enforceable, and neither a company's board nor the company, itself, is liable for damages if it fails to meet them" according to this piece in The Fashion Law. As it currently stands, the only consequence most brands face for failing to meet the criteria of these certifications is bad PR — which is usually as short-lived as the fashion cycle itself.

Legal liability, however, has a funny way of changing a company's sustainability claims. When a sustainably-minded company announced it wanted to go public via the first "sustainable public equity offering," they were ultimately forced to drop the statements by the Securities and Exchange Commission. A change that received little to no attention from the fashion media. Boring legal details that could lead to securities fraud might not seem newsworthy to the fashion press as the latest technology in mushroom fabrics, but regulators do care. New laws in the UK, Netherlands, and France suggest regulators increasingly care about those seemingly boring little details. Changing Markets Foundation is also tracking greenwashing claims.

Transparency is about removing the need to trust. The bottom line is that there's ample evidence that we can't trust most of what brands say when it comes to sustainability, but we can look at what they do.

What the Research Says About Quality

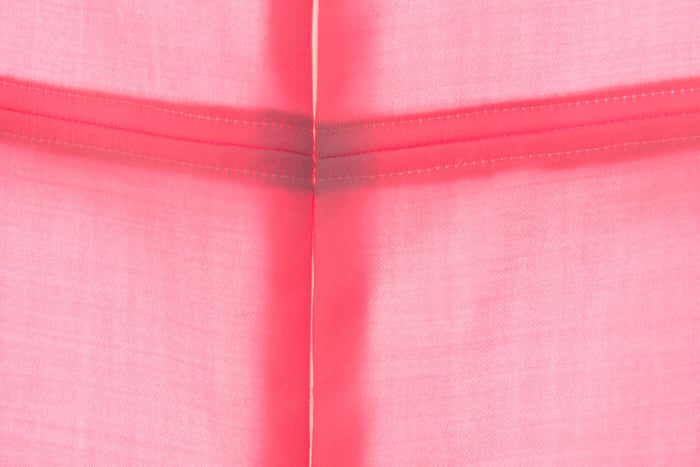

The type of fabric and how the seams are finished tell you more about a garment than any QR code or third-party certification. It's why at Senza Tempo you'll see photos of the inside of the seams and hem finishes on the website and social media. We often hear about the utility features and durability of technical or outdoor clothing, but rarely everyday or workwear.

Anyone can ascertain the quality of a garment by examining its fabric content, the hand and origin of the fabric, stitch count, and seam finishes. How quality is relevant to the true sustainability of a garment is also something a growing body of academic research supports.

The World Resources Institute notes that the majority of fashion's environmental footprint is in its Scope 3 emissions, the use phase. Brands claim that the use phase is out of their control. True, brands cannot control how many times or at what temperature a customer washes an item. But brands can control how well they make something and ultimately how well an item stands up during the use phase based on how well they make it.

This study found that general wear and tear (holes, rips, etc...) is why most people throw away their clothing. It's not because of new trends. Brands have chosen to make a higher number of poorer quality garments to drive bottom-line growth, not margin expansion. This is why apparel prices have lagged behind overall inflation. We've seen a race to the bottom in prices and quality.

Reuse is the most effective way to lower a garment's environmental footprint. This study of the circular economy compared the global warming potential of extended use, resale, recycling, and rental in fashion. The scientists found that extended use and resale have the lowest global warming potential. Every time you wear a garment, you lower the cost per wear along with the impact of the garment. Quality is essential to maximize the utility of a garment.

Mistra Future Fashion found that doubling the use of the average garment before disposal will lower its carbon impact by nearly 50% — more than any other measure a brand can take on the production side. Yet every other week I see more headlines about regenerative agriculture or mushroom fabrics — never anything about the features of the garments that will help them last longer.

All of this is common sense and basic math, but largely overlooked in the broader sustainability narrative. You can't greenwash quality and superior construction. It just is. Continuing to ignore it simply perpetuates the trends that have led to the current state.

Quality Checklist

The inside of a garment and how it's made and finished is as important as what it's made from. But there's more emphasis on whether a garment is made from the right buzzwords versus how it's actually made.

If we want to truly shop sustainably, we must shift our mindset to maximize the utilization rate of our clothing. Sustainability is not an adjective, it's a mindset. Fashion must return to the level of quality that was standard before the 2000s when globalization sent volumes up and quality lower.

The graph above illustrates global fiber production relative to the human population and the rate of change between 1975 and 2018. Between 1975 and 2000 the rate of change equaled 12.5, between 2000 and 2018 that rate nearly tripled to 35.6.

Source: The need to decelerate fast fashion in a hot climate - A global sustainability perspective on the garment industry, Greg Peters, Mengyu Li, Manfred Lenzen, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 295,2021,126390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126390

Making fabric out of nettles, pineapple, mushroom makes for great buzzy headlines, but how long will these fabrics last? Crooked seams and loose threads? That's a sign of workers forced to sew as many items as possible in the shortest amount of time. Often in deplorable conditions and pennies per item and those seams are weak and will fall apart easily. Using cheap polyester instead of more durable natural fibers saves a few dollars (or more) per garment is a marginal difference that adds up when you sell billions of units. In the past, a designer label used to be a marker of quality. Today, it's harder to identify which brands are doing quality work and which are simply great marketers.

Here are a few tips on what to look for:

- Country of origin (U.S., U.K., Japan, Switzerland, France & Italy are the highest quality manufacturers)

- Fabric Content (is it a natural fiber or polyester?)

- How does the fabric feel? How dense is the weave of the yarn? What is the weight of the fabric? Does the fabric feel soft and substantial or light and papery?

- Are the inside seams stitched tightly together or loose? Tight and dense stitch lines take more time to sew.

- Are the stitches even straight?

- Are there loose threads?

- Is there enough seam allowance to allow for alterations? Most Senza Tempo have a 1-1.5 inch seam allowance to allow for alterations.

- Is the garment lined and with what (a natural fabric like silk is preferable to polyester or acetate).

- Are there facings at the neckline and armholes if it's a sleeveless garment? This helps keep a garment structured.

- Is self-facing used around armholes, necklines, collars, pockets, cuffs? Facing creates a stronger, more durable garment, better drape, and prevents puckering around the edges.

A comprehensive list of attributes can be found here. You can find examples of what to look for here.

Country of Origin

The country of origin can tell you more about the quality than the name on the label. The highest-quality clothing is made in the U.S., Italy, Switzerland, Japan, France, Germany, and the U.K.

Senza Tempo is produced in a single atelier in downtown Los Angeles.

Fabric

What is the garment made of? Natural fabrics like cotton, wool, or linen have proven track records when it comes to durability. They are also breathable and can often be worn throughout the year depending on where you live and the weight of the fabric.

One thing to remember is that it isn't the wool that makes a suit hot in July, it's the polyester/acetate lining. Acetate is polyester, which is effectively plastic. Acetate isn't breathable or biodegradable. It's cheap though, and that's why it's so prevalent. A recent report from Changing Markets shows that the "sustainable" collections from many brands are 70% polyester.

Another thing to think about is how a fabric feels when you touch it: is it thin and papery, or soft and substantial? Is the fabric thin when it really shouldn't be? There has been a trend toward thinner fabrics because it saves money. Fabrics like voile, chiffon, or lightweight crepe de chines should be thin. Compare a polyester garment to one that's cotton or silk — notice how the fabric feels in your hand or how you feel the next time you wear the item.

Tip: Audit your closet to see what your favorite items are made of, how they are made and have worn over time.

Seams

Before you buy a piece of clothing, turn it inside out. How seams are finished is the most revealing part of a garment and the brand itself. As much care goes into finishing the inside of Senza Tempo garments as the outside.

Is the seam and stitch line straight? Look closely at the photo below. You can see how the stitch line follows the grain of the fabric.

Look at the stitches

How close are the stitches? The further apart the stitches the weaker that seam will be. Are there loose threads or does the inside have a clean finish like the photo below? I've seen loose serged seams and hems on a supposedly sustainable brand. Loose stitches aren't as strong and aren't likely to last. It's one of the easiest ways to cut costs since loose stitches reduce sewing time so workers can create more garments per hour. The very best made garments have tight stitch lines that finish the edge of the fabric, and/or seams covered by a strip of fabric so that the edges can't even be seen.

Is the edge of the fabric "bound" in some way? How much fabric is on either side of the seam? There should be at least ¼ of an inch to allow for alterations unless it's a knit where it would add bulk to the seam. Senza Tempo's social media regularly features photos of seams and the inside of garments along with the outside as a way to show and prove our quality. Quality is ultimate form of transparency.

Conclusions

Trying to shop more sustainably can seem like a tall order, though it's one regulators are trying to tackle. It's difficult for the average consumer to sort out which eco claims can be trusted and which are greenwashing. Most of the time the garment itself will tell you all you need to know without any information from the brand.

Stitch counts and fabric durability might not be quite as sexy or deemed as newsworthy as how to turn plastic bottles into a shirt, but that attitude must change to make meaningful progress toward creating a more sustainable fashion industry.

I’ve focused on quality when it comes to Senza Tempo’s “sustainability story” — in the past there weren’t sustainable and unsustainable fashion brands. Brands broadly operated more sustainably because clothing better reflected the true costs of production, which is why it was so expensive.

As consumers, we have to be able to look beyond the buzzwords. Don’t play Buzzword Bingo. Don't buy into these sustainable fashion myths. Simply, buy less and truly buy better. Science has shown that buying less makes us happier than buying green, anyway.